There is a photograph of a pile of pink and white paper hearts atop Mandi Koba’s Facebook page. She cut the hearts out of hard copies of a 1996 police report from Phoenix, Ariz. The cops, according to the vintage report used in the arts and crafts project, were investigating “a celebrity involved in a reported child molestation.”

Kevin Johnson was the celebrity. These days he’s a politician, a national figure with aspirations to the governorship of California who’s proclaimed himself “Little Barack” and worked closely with the Obama administration. Married to Michelle Rhee, face of the charter-school movement, he’s positioned himself throughout his adult life as a sort of catcher in the rye for at-risk inner-city children through his work with a variety of charter schools and foundations, setting him up for his current run as the scandal-prone mayor of Sacramento, Calif. In 1996, though, he was one of the NBA’s top stars, at the very height of a career with the Phoenix Suns that saw him make three All-Star teams and earn tens of millions of dollars.

Mandi Koba, 15 years old at the beginning of the events described in the report, was the child.

In time, there would be a fair amount of public discussion of the allegations made in that report, which involved Johnson fondling the teenager, showering with her, rubbing his genitals against her bare thigh, suggesting they pray together and ask for forgiveness, and making the only child from a single-parent home give a “pinky promise” that she wouldn’t tell her friends or mother what he’d done. But the investigation produced no physical evidence that any crime had been committed, no criminal charges were ever filed against Johnson, and the accuser never spoke out.

A year after prosecutors decided not to indict, word about Koba’s molestation allegations got out around Phoenix. In May 1997, the Phoenix New Times reported that a lawyer representing the girl was trying to get money out of Johnson. Koba was not named—the pseudonym “Kim Adams” was used—but she took a beating in the story. Attorney Fred Hiestand, an advisor to Johnson at the time and to this day, told the paper that the Suns’ supernova point guard had indeed spent time with the accuser, but only because he’d “tried to help” her. Paul Rubin, the reporter who broke the bombshell story, wrote that Hiestand characterized the accuser as “mentally unstable and a liar.” Later, he would write that a Johnson lawyer had described Koba to him as a “sick slut” during his original reporting process.

“If he was interested in any kind of sexual action,” Hiestand told Rubin, “he had a lot more attractive offers.”

(Fred Hiestand—currently listed as president of two of Johnson’s non-profits, the Sacramento Public Policy Foundation and the St. HOPE Endowment—did not respond to repeated requests for comment.)

Johnson’s camp, it should be noted, was attacking a high school kid who, according to the police report, weighed 95 pounds.

Hearts Mandi Koba cut out of a 1996 police report. Photo via Focus Photography

Johnson retired from the NBA in 2000 and left Phoenix for Sacramento, where he went into politics and became mayor of his hometown. He’s since faced sexual-abuse accusations every so often. These allegations have been made by different people in different places and at different times, but tend to follow a very similar pattern. They’ve involved Johnson being in positions of trust—often within institutions he’s controlled—and young girls, who are sometimes underage. He’s always stayed clean, with the same lawyers by his side, but the Phoenix case remains notable. Not only was it the first time such an allegation was raised against Johnson, it remains the deepest investigation yet into his dealings with young girls.

The accusations in this report have followed Johnson for years, coming up in different contexts as he’s made his way in the world, but they’ve never seemed to have any serious effect on his standing or reputation. Part of the reason for this is that his accuser, Mandi Koba, has never publicly talked about the case. Her silence, however, had nothing to do with that pinky promise.

“I wasn’t allowed to talk about it,” she tells me.

Koba says that she stayed quiet because, not long after the New Times story was published, she took Johnson’s money in exchange for a pledge to never mention Kevin Johnson ever again except to “a priest, a therapist, or a lawyer.” She says that there is only one signed copy of the agreement she made with Johnson, locked away in a safe deposit box in Arizona. The box, she says, “can only be opened when both of our attorneys are present.” She assumes that he’ll come after her for any violation of the pact it holds.

(Ben Sosenko, Johnson’s press secretary at City Hall, did not return emails requesting comment.)

The celebrity from that police report remains a celebrity, soon to be fêted by ESPN with a documentary playing up his role in keeping the NBA’s Sacramento Kings from leaving town, but the child is no longer a child. Koba was 15 years old when she met Johnson, and still a teenager when she sold the right to talk about him—and about her own life. The pile of cutout paper hearts is but one of many indications that she’s still haunted and even defined by the parts of her life with him in them.

She’s 36 now, though. She lives in Virginia, far away from Arizona, and has three young children of her own. And she’s done staying quiet about Kevin Johnson.

“I’ve chosen to say what I want, fully aware of the consequences,” she tells me.

“I just felt like I wasn’t doing anything but protecting him,” Koba says of her years of silence. “Part of the way they got me to go along with the agreement was they told me it would protect me from his attorneys saying mean things about me. Well, I’m a grown-up now. They can say mean things about me if they want.”

“I kind of turned myself off and I was just kind of laying there.”

The original police report from the 1996 investigation into Johnson lays out a portrait of a sexual predator grooming a victim so broadly familiar in its details as to verge on cliché. It says that Koba met Johnson in 1995 while shooting a TV commercial aimed at reducing gun violence. She’d been recruited by her boss at the Phoenix Department of Parks and Recreation, where she was working on an anti-gang initiative, to serve as an extra in the PSA. Converse sponsored the production, and Johnson, who had his own line of shoes with the company, was cast as the star. Koba told police that Johnson gave her his business card soon after the shoot, and sent flowers to her home for her 16th birthday.

She now says that everybody was starstruck when Johnson came over to meet her mother and tell her that her daughter had great potential in need of nothing more than someone who could tap it, and that with no father in her picture, he could be that someone. “I grew up with a Kevin Johnson poster on my kitchen door,” she says. “We had season tickets.”

Kevin Johnson drives on Michael Jordan in the 1993 NBA Finals. Photo via AP/Jon Swart

So Mom gave Johnson, then 29 years old, her blessing to mentor her daughter, with one caveat.

“She told him he couldn’t be my boyfriend,” Koba now says. “She told me the same thing.”

(Mandi Koba’s mother could not be reached for comment.)

The transcript of her 1996 interview with the Phoenix Police Department has her telling police she was lacking a “father figure” when Johnson showed up. He gave her a pet name, she told police: “Whiskey.”

“And when he hasn’t seen [me] in a while or talked to me,” she said, “he’d leave a message telling me that he needed a shot of whiskey.”

One of her first talks with Johnson, she told police, involved her telling him all about “water balloon fights out on the street.” Koba all but stopped seeing friends from Arcadia High in Scottsdale that summer, and instead spent her time hanging out with Johnson. Among the outings listed in the police report, Johnson took her to see Batman Forever in a theater and rented The Last Seduction for them to watch at her home.

“She was very smart, and beautiful, and had a lot of friends, but she basically just dropped out socially and was with him all the time,” says a high school friend of Koba’s. “It was all very secretive and weird. We’d ask what they were doing, and she told us they’d just read the Bible together. There was a whole lot of the Bible.”

She told the police, however, that he began taking her to different properties he owned in the Phoenix area, and that that this is when the molestation started.

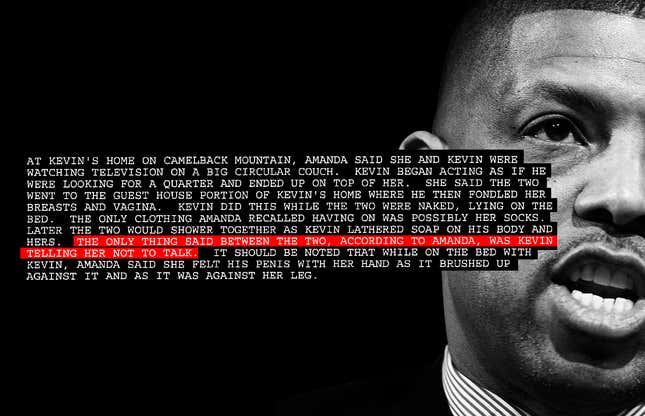

From the report:

Although the physical contact between Kevin and Amanda started with just massages of her feet and taking her hand while talking, it escalated, according to Amanda to events that made her feel bad.

At Kevin’s home on Camelback Mountain, Amanda said she and Kevin were watching television on a big circular couch. Kevin began acting as if he were looking for a quarter and ended up on top of her. She said the two went to the guest house portion of Kevin’s home where he then fondled her breasts and vagina. Kevin did this while the two were naked, lying on the bed. The only clothing Amanda recalled having on was possibly her socks.

Later the two would shower together as Kevin lathered soap on his body and hers. The only thing said between the two, according to Amanda, was Kevin telling her not to talk. It should be noted that while on the bed with Kevin, Amanda said she felt his penis with her hand as it brushed up against it and as it was against her leg.

Another time, she told a detective, they met up at a local park, took a short drive, and parked. He fondled her stomach and breasts for 15 to 20 minutes as she wore nothing but socks and a long sweatshirt he’d asked her to wear.

“After,” she said, “I mean I kind of turned myself off and I was just kind of laying there.”

The police report indicates that law enforcement was tipped off to Johnson’s alleged behaviors not by Koba, but by a therapist who had been working with Koba because she was suffering a serious eating disorder. Before going to the police, though, according to the report, the therapist had, bizarrely, gotten in touch with Johnson and told him that Koba and she had discussed their having sexual contact, which the therapist related to the eating disorder. Koba now says that police weren’t thrilled by the therapist’s actions, and that their investigation was compromised by that approach. However, investigators nevertheless went forward with a “confrontation call,” having Koba phone Johnson on a secretly tapped line to try to get him to talk about their dealings. The police report contains a transcript of that conversation. In it, Johnson comes off as guarded, but it nonetheless speaks for itself:

Koba: “Well, I was naked and you were naked, and it wasn’t a hug.”

Johnson: “Well, I felt that it was, you know, a hug, and you know, I didn’t, to be honest, remember if we were both naked at that time. That is the night at the guesthouse?”

Koba: “Yeah. ... Why would I be upset if it was just a hug?”

Johnson: “Well, I said the hug was more intimate than it should have been. But I don’t believe I touched your private parts in those areas. And you did feel bad the next day and that’s why we talked about it.”

Koba: “Well, if it was just a hug, why were either one of us naked?”

Johnson: “Again, I didn’t recall us being a hundred percent naked.”

Koba told police that Johnson stopped taking her calls or returning pages after the confrontation call. She says now that she always felt like the cops believed her and worked hard to build a case, and there is evidence of that in the police report. A transcript shows that during one lengthy interview, a detective told her, “I think he’s taking advantage of you because of his celebrity status and I think he’s probably taking advantage of other young people.”

The Phoenix police filed their report with prosecutors in Maricopa County, who told Koba by mail that they would not pursue the case. She asked for a reconsideration, but got the sense that a staffer in the district attorney’s office was just trying to get her out of the room.

That staffer, she says, told her that while her story was credible, the decision to not prosecute was made in part because of a lack of physical evidence and in part “because of who he is.”

Koba has not heard from Johnson since around the time of the settlement, which she says compelled him to “apologize telephonically” to her for any harm she suffered, while denying any responsibility for that harm. She has heard from Johnson’s attorneys, however. She takes macabre pleasure in recounting one of those contacts.

“He tried to get me to pay for the safe deposit box,” she says. “Really. He’s absolutely unreal. It was like $18 a year, and they would send me the bill.”

Did you pay it?

“Hell, no.”

“I didn’t want to use his money for anything good in my life.”

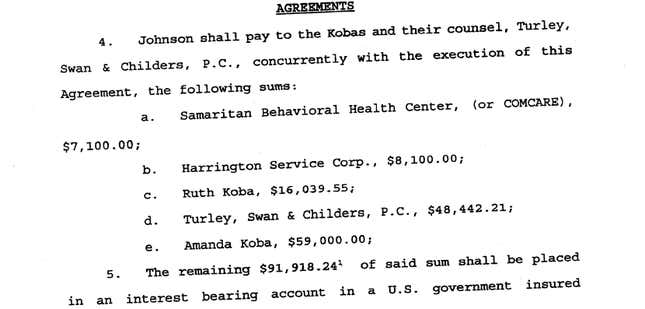

Mandi Koba asserts that Kevin Johnson paid precisely $230,600 for her silence.

This is the figure you get when you add up the numbers on the first page of what she presents as an unsigned copy of their agreement that she got from her lawyer when he retired. (It tracks the $230,000 figure reported in the Sacramento Bee in 2008.) While this document played a pivotal role in her life, Koba didn’t know the total amount off the top of her head, because legal fees, a payment to her mother, and hefty health care costs from mental injuries she attributes to what Johnson did to her ate into the sad windfall. Her original payment was $59,000, with another $91,918.24 put into a trust in her name.

A detail from what Mandi Koba asserts is an unsigned copy of a 1997 agreement between her and Kevin Johnson; a fully executed version, she says, remains in a safe deposit box.

Koba says that the money went fast. She left Phoenix two months after the settlement to go off to the University of San Francisco, and wonders now what those years would have been like had she arrived on campus as a “normal girl.” She lasted a semester, and says she dropped out because she was obsessing over how her tuition was being paid with Johnson’s blood money.

“I didn’t want to use his money for anything good in my life,” she says. “I didn’t want to think, looking back, that my college degree was with his money.”

Koba says she moved back home, intent on spending the settlement on “meaningless things.” When it was all gone, she enrolled at the University of Arizona, and in 2003 got a BA in women’s studies. I ask if she can recall any specific purchase she made; she says she can’t.

She can, however, give a litany of afflictions she traces to her encounters with Johnson, none uncommon among sexual-abuse survivors: severe trust issues, an eating disorder that required hospitalization, bad relationships with men, and more. She has yet to share or enjoy her kids’ growing love of sports, and fears she never will. She’s not sure she’s right to scold them whenever she feels they’re celebrating a professional athlete, such as by asking her to buy them a basketball player’s signature shoe, but can’t help herself. She says that her relationship with her mother, whom she is unable to forgive for not protecting her from Johnson, “will never heal.”

And she reports other invisible wounds. Perhaps most surprising, she says, is how acute and damaging her memory of Johnson’s scent still is.

“If I smell anything like what he smelled like, it’ll take me right back to being abused,” she says. “That still happens. I still have that memory.”

“Mr. Johnson ‘said all he needed was my savings account number.’”

The past comes back for Koba whenever she reads about Johnson being accused of messing with kids. That’s not too rare. A 2008 story in the Los Angeles Times about Johnson’s first run for mayor mentioned that Johnson had overcome allegations that he “molested a 16-year-old girl named Mandy in 1995.” The Times reporter wrote that Fred Hiestand, Johnson’s fixer, said that “his accuser was mentally unstable and had been swayed by a zealous therapist.”

That same story also went over accusations that in 2007 Johnson had molested a student at St. HOPE, the charter school he founded in Sacramento. But Hiestand, who had trashed Koba more than a decade earlier in Phoenix, showed up to assert, as the reporter described it, that “the girl’s words had been twisted by the teacher who reported the allegations.”

Erik Jones was the St. HOPE teacher who went to police in 2007 after a student told him that she and other kids at St. HOPE had been molested by Johnson. Last year, he told me that he had never twisted anybody’s words. Here’s a portion of a suspected child-abuse report he filled out after the alleged incident was described to him:

On Monday April 23, [REDACTED] relayed the following information to my self (Erik Jones), Jill Tabachnick, Dora Bromme, and Lisa Wood:

“Mr. Johnson [a teacher and President of St. HOPE publics Schools] came up behind me and started to massage my shoulders. Soon his hands were on the top of my breasts. The situation grossed me out and that was not the first time. He has, on numerous occasions, hugged me and kissed me either on the cheek or on my forehead. He is a family friend, but I feel creeped out when he does this. He has also done this to other girls in the class and with one of the Hood Corps students he tried to crawl into her bed. And that is why she quit Hood Corps.”

No charges were filed in that case. According to the Sacramento Bee, police never interviewed Johnson, who was running for mayor and also serving as principal of the school when news of the accusations broke. His campaign released a statement to the paper saying that the school had put together “[a]n impartial three-person panel” to investigate the accusations, and “found that the allegation was unfounded.”

The leader of the impartial panel? Kevin Hiestand—Fred Hiestand’s son.

(Kevin Hiestand, who at one point served as chairman of the board of St. HOPE Academy and was later treasurer of Johnson’s campaign for re-election as mayor, didn’t return emails requesting comment.)

According to a 2008 report on St. HOPE by the Corporation for National and Community Service—the federal agency that, among other things, oversees AmeriCorps—Jones told investigators that Kevin Hiestand, who is also an attorney, had tried to get him to change his story. The Bee reported—in a story included in a Congressional report on the firing of the man who ran the CNCS investigation—that a student corroborated this version to one of their reporters:

The classmate, Dora Bromme, said Hiestand pulled her out of class and told her the girl making the allegation had recanted. In an interview, Bromme told The Bee that Hiestand said he was from “human resources” but did not identify himself as a lawyer.

She said Hiestand told her that the student “told us that (Johnson) just kissed her on the forehead and gave her a pat on the shoulder and left.”

“I said to him ‘I can tell you for a fact that’s not what she said,’’’ Bromme said. “He was changing around the story.”

Jones quit teaching at the school in protest, and in his resignation letter wrote, “St. HOPE sought to intimidate the student through an illegal interrogation and even had the audacity to ask me to change my story.”

Jones remains bitter about how the school handled accusations against its founder.

“Kevin Johnson said education is the civil rights movement of the 21st century, and I believed it,” Jones says. “I thought he wanted to make lives better.”

Jones’s resignation story was not the only molestation allegation against Johnson that surfaced during the CNCS investigation of St. HOPE, which was carried out by Gerald Walpin, the agency’s inspector general. Walpin was primarily looking into charges that Johnson was using grant money for personal uses, and reported “false and fraudulent conduct in connection with $845,018.75 in Federal funds.” But his report on St. HOPE also included allegations of inappropriate sexual conduct made against Johnson by five young women.

No names or ages for the accusers were given, but Walpin wrote that Johnson’s behavior could “seriously impact … the security of young [AmeriCorps] Members” that had volunteered for Johnson’s non-profits. A Congressional report on the investigation said Walpin’s findings “give rise to reasonable suspicions about potential hush money payments and witness tampering.” One alleged victim, according to the report, told investigators that Kevin Hiestand had “basically asked me to keep quiet,” and that Johnson later “offered her $1,000 a month.”

“As [REDACTED] related that conversation,” the report states, “Mr. Johnson ‘said all he needed was my savings account number,’ he would make the deposit and ‘no one needed to know about it.’”

Kevin Johnson at a press conference in Sacramento, 2012. Photo by AP/Rich Pedroncelli

The report also details how charter-school activist Michelle Rhee—then a board member at St. HOPE and Johnson’s future wife—served as “a fixer, doing ‘damage control.’” A St. HOPE staffer, Jacqueline Wong-Hernandez, told investigators that shortly after she alerted Rhee that a student had accused Johnson of sexual misconduct, Kevin Hiestand visited the accuser and the matter then went away. Wong-Hernandez, like Jones, quit her job at the school in protest.

(Rhee is again on the St. HOPE board of directors; neither she or a representative responded to repeated requests for comment.)

Johnson paid a large fine to the federal government to settle the financial claims brought up by Walpin, but no criminal charges ever grew out of the sexual-abuse allegations.

Koba admits to having kept up with Johnson through the years, and to having followed the fallout from the Walpin report. I ask what goes through her mind when she reads that other kids are making allegations against Johnson similar to those she made as a teenager.

“I did feel validated,” she says. “And I felt horrible.

“For the longest time, I would feel that it was my fault—I hadn’t done enough to stop him,” she says. “I know that’s ridiculous. I couldn’t stop him. But I felt responsible for their pain. I don’t know who they are, and they likely cannot tell anybody but their therapist or the priest or attorney.”

“It’s time.”

Mandi Koba has never used her real name to enter into any public discussions of Johnson.

But it’s been out there for anybody to find. Because of a lazy or uncaring redactor, the name “Amanda Koba” is in the 1996 police report, which has been circulating around the internet for years. So anybody who sifts through all the sleaze found in those pages can learn who Johnson’s original accuser was.

And over the last year, Koba has quietly made it easier to find her. In January, she published a personal essay, under the byline Mandi Koba, on a website called The Unslut Project, which gives as its mission statement, “Working to undo the dangerous ‘slut’ shaming and sexual bullying in our schools, communities, media, and culture.” Johnson’s name doesn’t appear anywhere in Koba’s piece, but from the title—“My Silence Has Been Bought. My Story Is Not My Own”—on down, it’s otherwise loaded with everything she was paid by her alleged assailant not to talk about.

Here’s the opening paragraph:

“I am every victim of sexual assault by a celebrity, a professional athlete, a politician, who has been silenced. I’ve been afraid to speak, come forward and tell my story. But no more. It’s time.”

What follows is a searing description of being “intoxicated by... the attention, the specialness that draws people to the energy of the well known and celebrated,” of being “conned” and “accepting the unwanted touch of a grown man I trusted, believed in, thought believed in me. An adult mentoring me, grooming me, promising me the world if I would just trust, trust in him.”

“I’ve been called a sick slut in the media, a gold digger, an unreliable victim,” Koba wrote. “I’ve had attorneys infer that the man who abused me had much more attractive women, options, so the idea that he’d sexually abuse me, a minor, was ludicrous. I’ve had my perpetrator - that’s what he is, a perpetrator, not someone who just made a mistake - held up as an example, a leader, a trusted advisor.”

In the piece, she also admits to taking money from her assailant.

In the spring, she posted several photos of the pink and white paper hearts on her Facebook and Twitter. She even explained to an admirer where the paper came from: “Those hearts were repurposed from a very painful, negative police report into something joyful. Better than money.”

Mandi Koba. Photo via Focus Photography

Koba has also started up her own blog, at mandikoba.com, that she designed as a clearinghouse for sexual abuse survivor stories, including her own: In June, she reposted her piece about being paid off by the celebrity who molested her.

All in all, it’s as if she wanted to be found—and a matter of practicing what she preaches. Koba now volunteers as a crisis responder for sexual assault victims through Rappahannock Council Against Sexual Assault. In that role, she visits emergency rooms of local hospitals when rape kits are being administered to serve as a liaison between victims and law enforcement and to “hold hands” when anybody needs it.

Mostly, she’s there if somebody wants to talk about what happened to them. She says what she experienced as a kid helps her deal with victims as an adult, and that she’s pleased that the world is a better place for young victims now than it was when she told the police Johnson had molested her. No lawyer, for example, would dare trash a juvenile accuser in the media today the way Johnson’s machine trashed her nearly two decades ago.

But, she says, on the job she’s realized the legal system remains imperfect. She says she recently was in an emergency room and witnessed a police officer who she believes was sincerely concerned about the well-being of a girl who’d been raped tell her that “she shouldn’t have gone to the boy’s room.” And no matter how much nicer the world is for those who suffer sexual abuse now than it was 20 years ago, Koba says that she believes a child seeking justice against a celebrity of Kevin Johnson’s stature would fare no better now than then.

“Oh, he would totally get away with it now,” she says. “He totally would.”

Koba recently filmed a public service announcement, just as she’d done as a 15-year-old on the day she first met Kevin Johnson. This one, however, had a different purpose. It was aimed at convincing victims of sexual abuse not to stay silent.

Do you have a story to tell about Kevin Johnson? Contact the reporter at dave.mckenna@deadspin.com or use our SecureDrop system for extra security. Top image by Jim Cooke, with photo via AP and text via Phoenix Police Department.